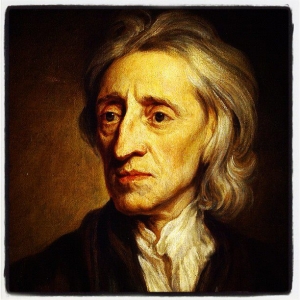

The interweb is a funny thing. One never knows what, at any given moment, one will discover. This morning I stumbled on a discussion involving David Harsanyi editor at one of my favorites, The Federalist, over John Locke (1632–1704), God, and natural rights. The thread was difficult to follow (one of the weaknesses of Twitter) but Harsanyi seemed to be suggesting that Locke did not believe that rights come from God. Please note the qualification, seemed. This discussion came out of his defense this morning of Ted Cruz’s idealistic and “God-heavy” announcement of his candidacy for the office of President of the United States. Harsanyi writes,

The interweb is a funny thing. One never knows what, at any given moment, one will discover. This morning I stumbled on a discussion involving David Harsanyi editor at one of my favorites, The Federalist, over John Locke (1632–1704), God, and natural rights. The thread was difficult to follow (one of the weaknesses of Twitter) but Harsanyi seemed to be suggesting that Locke did not believe that rights come from God. Please note the qualification, seemed. This discussion came out of his defense this morning of Ted Cruz’s idealistic and “God-heavy” announcement of his candidacy for the office of President of the United States. Harsanyi writes,

The Declaration of Independence states, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” This founding document informs the Constitution, which restricts government from meddling in important areas of our lives. That’s how the Founders saw it. That’s how we’ve pretended to see it for a long time. Some of us believe that these natural rights, divine or secular, are universal, that they can’t be repealed or restrained or undone by democracy, university presidents, or rhetorically gifted presidents.

If that’s God’s position – or, more specifically, if enough people think that’s His position – well then He’s my co-pilot, as well.

Even though Harsanyi, a self-identified atheist, finds Cruz’s rhetoric a little too religious for his tastes, if he has to choose between those elites who cluck at traditional American rhetoric about rights coming from God and Cruz, he’s happier with Cruz.

On one side of the deep cultural divide, the very notion that God tells us anything is silly. That’s why you see many journalists react with confusion or with contemptuous tweets or feel the need to highlight something so obvious. On a political level, the idea that God can give us unalienable rights only threatens an agenda that doesn’t exactly hold your right to live in peace without interference sacred. And this lack of reverence for rights will lead to a serious battle between religious freedom and progressive aims.

Harsanyi’s invocation of Locke this AM puzzled me—it’s been a long time since I read Locke’s Second Treatise but thanks to the good folks at the Liberty Fund both his First Treatise and his more familiar Second Treatise are easily accessible online. My political science profs (one of them at least, the fellow whose lectures made me want to major in poli sci) used to say that when Locke and his contemporaries wrote about God they were kidding. After re-reading bits of the Two Treatises (1689) I was surprised to find that much of the First Treatise was a detailed exegetical commentary on Genesis 1. Repeatedly in both treatises he treated Adam and Eve as historical figures. He refers sincerely to God more than 300 times. Hence the reference to fundamentalism. In today’s climate, a political theorist who wrote about God as if he really is and Adam and Eve as if they actually were would be regarded as having a slippery grasp on reality or as a fundamentalist of some sort. Doubtless snide references to the Christian Taliban would soon follow on Twitter.

Consider this passage from Locke’s First Treatise.

Man being born, as has been proved, with a title to perfect freedom, and an uncontrouled enjoyment of all the rights and privileges of the law of nature, equally with any other man, or number of men in the world, hath by nature a power, not only to preserve his property, that is, his life, liberty and estate, against the injuries and attempts of other men; but to judge of, and punish the breaches of that law in others, as he is persuaded the offence deserves, even with death itself, in crimes where the heinousness of the fact, in his opinion, requires it. But because no political society can be, nor subsist, without having in itself the power to preserve the property, and in order thereunto, punish the offences of all those of that society; there, and there only is political society, where every one of the members hath quitted this natural power, resigned it up into the hands of the community in all cases that exclude him not from appealing for protection to the law established by it. And thus all private judgment of every particular member being excluded, the community comes to be umpire, by settled standing rules, indifferent, and the same to all parties; and by men having authority from the community, for the execution of those rules, decides all the differences that may happen between any members of that society concerning any matter of right; and punishes those offences which any member hath committed against the society, with such penalties as the law has established: whereby it is easy to discern, who are, and who are not, in political society together. Those who are united into one body, and have a common established law and judicature to appeal to, with authority to decide controversies between them, and punish offenders, are in civil society one with another: but those who have no such common people, I mean on earth, are still in the state of nature, each being, where there is no other, judge for himself, and executioner; which is, as I have before shewed it, the perfect state of nature. (ch. 6, §87).

This language comes after a lengthy, detailed discussion, including exegesis of the Hebrew text, of Genesis 1. He was arguing about whether monarchy can be proved from Adam and Eve. He referred, in the Two Treatises, to the Adam of the biblical creation narrative 410 times. The passage above, read without reference to its context, gives one impression. Read in context, however, it leaves another. In that regard it’s interesting that my poli sci profs assigned the Second Treatise (I think I read it a couple of times) but never the First. There are plenty of references, however, to God, Adam, and Eve in the Second Treatise.

Jefferson’s reference to “nature’s God” may well have been intentionally Deist but it’s clear in Locke’s First Treatise that the God of nature, who gave the law of nature, by which civil society is to be ordered, is the God who has revealed himself in Scripture and in nature.

Please do not misunderstand. Locke was no bastion of Reformed orthodoxy. He was more comfortable with the Remonstrant Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) than Cocceius or Witsius. He referred to Grotius but not to the orthodox Reformed in the Two Treatises. His defense of Christianity, The Reasonableness of Christianity, made that clear. Nevertheless, it’s also clear that Locke was writing at the end of the period of Reformed orthodoxy and his frame of reference was at least influenced by categories with which we are familiar. Students of Reformed federal theology (covenant theology) will see in Locke echoes of the Reformed discussion of the covenant of works.

Locke’s influence on the American founders can hardly be denied. When he writes of life, liberty, and the pursuit of private property—he repeatedly used the expression “life, liberty, and estate” or variants—it sounds almost as if the Founders retroactively wrote some Lockean passages. It’s a good reminder of our national cultural, political roots. This is not an apology for Constantinianism nor “Christian America” but re-reading a bit of Locke this morning reminded me that Christian influences on the founding of the Republic were significant and that our founders drew from wells influenced by Reformed categories and thinking. T’hat history suggests that we do have a place here and that the upside-down culture in which we live, in which “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” is said to be the grant of government, is not true to the intent of our founders as understood against their intellectual background.

This post reminded me of an address a few years ago given by George Will at the Danforth Center on Religion and Poltiics. Will, an agnostic and the son of a Lutheran minister, questioned whether democratic freedoms were sustainable absent an underlying religious basis for natural rights. He suggested that the question remains open, but the early returns do not look promising.

One of the more interesting moments of his appearance occurred during the Q&A when an earnest student suggested, based on Will’s thoughts about the possible necessity of religious belief to freedom, that he should become a religious believer for utilitarian reasons. Will, rightly I dare say, declined to accept Christian views on a utilitarian basis.

George Will is the grandson of a Lutheran pastor. George’s dad was a philosophy professor and author.

Rubin, thanks for the correction.

I have been interested in this topic ever since I read Francis Schaeffer’s assertion that Locke borrowed from Samuel Rutherford’s _Lex Rex_. I got around to reading both Locke and Rutherford, and while I’m not sure that there’s a dependence on Rutherford himself in Locke, I can see why Schaeffer said what he did. Although Locke was more comfortable around Remonstrants, he was raised in a Puritan home, and ideas like Rutherford’s were “in the air” in his childhood and youth.

Also, I doubt that Locke was “just kidding” when he was talking about God. It seems to me your pol sci professor may have been influenced by Leo Strauss–of whom I hold the strong suspicion that he played the agnostic/atheist sophisticate while, deep down inside, he remained something of a Jewish believer.

Rutherford was also one who doubted that it was possible to find the true heir of Adam (necessary if the unfortunately named “patriarchialist” position of Robert Filmer and his predecessor John Maxwell, Rutherford’s target, is to hold). He asks how, if the Maxwell (and later, Filmer) position is true, how Nimrod could be the first king while Shem was probably still alive. He notes as well that while the state may put a man to death for crime, that is not a power of the father. However, an important consideration in reading Rutherford (admittedly turgid and dense, not at all like his letters) is to recognize that he firmly believes that government is divine in origin, even if popular in mode (he sees the Constitutions of both British kingdoms as fundamentally mixed, rather than strictly monarchial).

While some of this seems to anticipate Locke, Rutherford would’ve been the first to admit that he was part of a whole crowd of Reformed political thinkers with similar ideas: Beza, Althusius, Hotman, “Junius Brutus”, John Ponet, Christopher Goodman, etc. etc. etc.). Even though Calvin, in Book IV of the ‘Tutes, argues that the _mishpat hammelek_ of I Samuel 8 is a “ius regnorum” (“right of the king”), he nonetheless expresses preference for a mixture of Democracy and Aristocracy; in contrast, Rutherford is the better Hebraist, and argues that the _Mishpat Hammelek_ is “the manner of a king”.

Well, I’m a little too tired to continue.

While there is a very strong case to be made that Locke believed in a god (as seen in The Reasonableness of Christianity), the idea that God revealed himself in history would be for Locke, perhaps a bit misleading.

I suspect that your political science professor would have directed your attention in Locke’s First Treatise to his comment that “reason is our only star and compass.” We see Locke using reason as the arbiter of truth in the Paraphrase and Notes on the Epistles of Saint Paul; a helpful passage is something like his comments on I Corinthians 2, where the text becomes wiped clean of the notion that it really is impossible for the natural man to understand the truth about God. Speaking of clean, his notion of the tabula rasa would also perhaps suggest to your political science professor that Locke’s rationalism was such that he eschewed any notion of original sin and all that sinfulness means for our ability to comprehend the things of God. What this means to your political science professor is that although Locke may use the Scriptures frequently, he cannot possibly be using it as a necessary means of understanding the things of God – but perhaps at best, he uses them as an aid to augment what is generally discoverable by reason alone. So while Locke has some kind of reverence for the Scriptures, this reverence is not very great, and reason is the only test of its reasonableness.

The founding was much more influenced by Christian ideas than some kind of radical secular revisionist is willing to admit, but we don’t need Locke to make that case.

Approaching Locke from the perspective of someone who read the Two Treatises without the benefit of commentary by a modern political science prof, it seems that Locke approaches Scripture in a way not unusual among scholars of his day who weren’t theologians, be they medical doctors or whatever. To use a modern term, it’s an assumed part of their “worldview”. The same is true of founders like Jefferson or Franklin, the case has been made that they weren’t Christians, but on the other hand some of their statements are so orthodox that they shame those made by some modern reformed ministers. As it’s obviously anachronistic to read modern debate about origins or fundamentalism into the statements from those generations, I can’t help but find some of the avoidance and cringing by modern liberals when they encounter some of these statements a little amusing…or cringe myself when Mr Barton presents some of his material….